TLDR;

Keywords: Children’s Fiction, Classics, Fairy-tale-ish, Adventure, The Granddaddy of High/Epic Fantasy

Recap: A classic tale of hero’s journey, supported by some fantastic world-building, that was meant as a fairy-tale for children

Rating: 2.5 out of 5 (hear me out)

Read if you:

Wants a fun and easy introduction to fantasy novels

Enjoys a classic hero’s journey story

Loves amazing epic fantasy world-building

Interested in the roots of modern epic fantasy

The Origin of Modern Fantasy

“In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.”

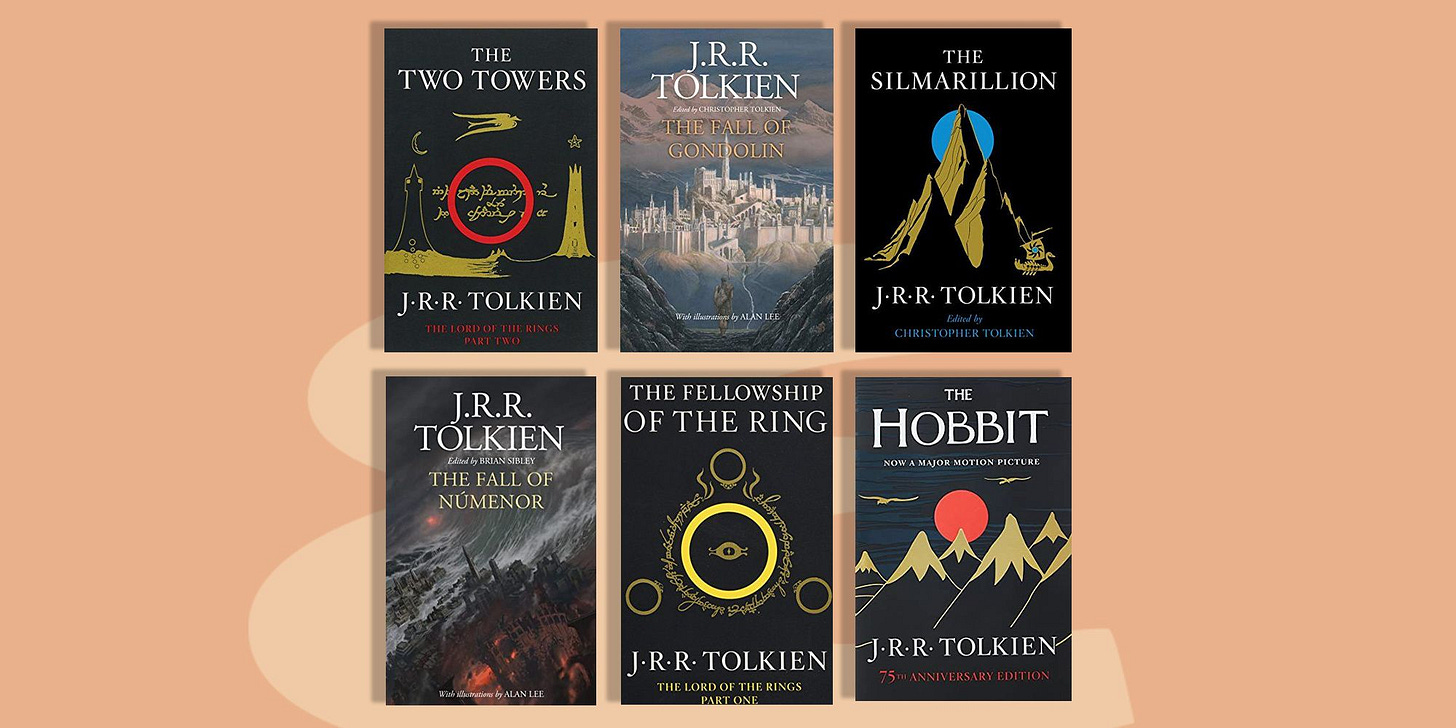

It is really difficult to overstate the influence J.R.R. Tolkien’s influence on modern fantasy. Modern fantasy can be divided into three phases: Pre-Tolkien, Tolkien, and Post-Tolkien.

You have undoubtedly consume numerous media that have been inspired by his works:

Books & Movies: Harry Potter, Game of Thrones, Chronicles of Narnia, Star Wars

Games: Dungeons & Dragons, The Legend of Zelda, Dragon Quest, Final Fantasy

If you are familiar with the race of Elves in fantasy (beautiful, pointy ears, basically immortal, good at archery), that image of Elves literally did not exist prior to J.R.R. Tolkien’s works—he created Elves as popularized today through a combination of various mythological interpretations of elves in different cultures.

Tolkien’s impact on modern fantasy all started with The Hobbit, also known as There and Back Again, published in 1937. The book was written as a children’s novel dedicated to Tolkien’s own children, before being expanded upon nearly 20 years later in 1954 through the epic fantasy of all epic fantasies The Lord of the Rings.

I’m new-ish to fantasy novels, and so I felt like The Hobbit is a necessary rites of passage any fans of fantasy books must read through. I also wanted to read it before reading The Lord of the Rings trilogy later on.

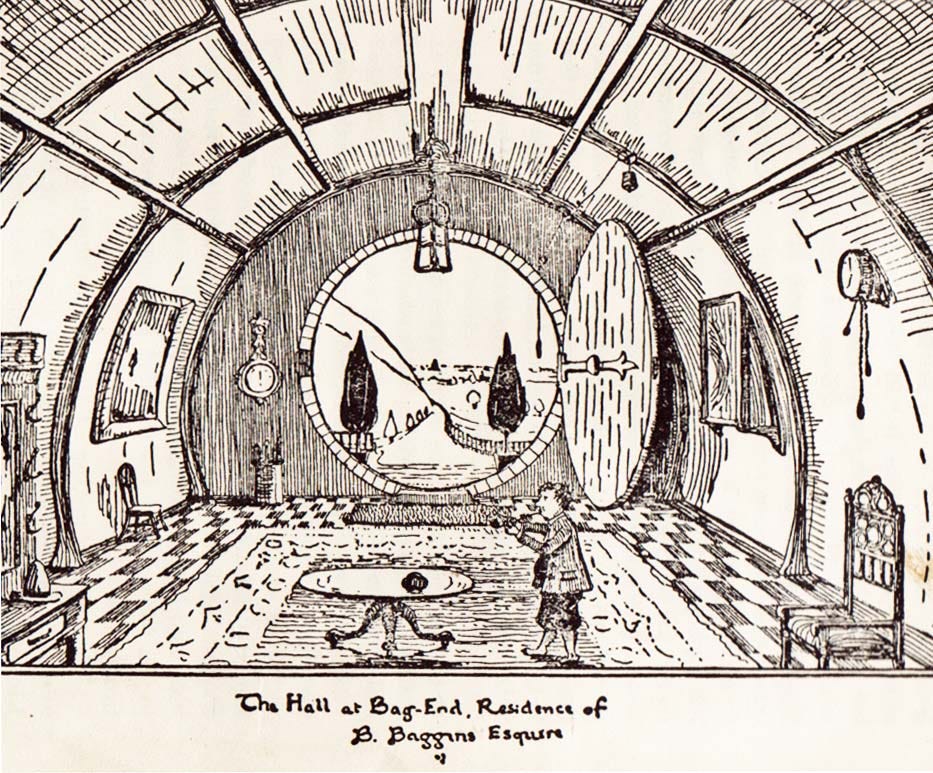

What really amazed me is the world-building. The depth of it, and the obvious amount of scholarship Tolkien has put into creating this world. It’s amazing how much detail and life Tolkien gave to this world in just less than 400 pages.

However, I have to admit that the book wasn’t quite as transcendent as I imagined (maybe I set the bar too high?). It definitely wasn’t as easy to finish as I hoped.

Hear me out: it is obviously a children’s book, and the prose used is most certainly so. The plot is also relatively straightforward, as is common with works meant for children. The characters also fairly two-dimensional without much characterization or growth to them.

Maybe if I read this book when I was younger, it would be different. Nevertheless, it doesn’t take much away from the world-building Tolkien has set up, and its subsequent impact on modern fantasy.

Fantastical world-building that packs a punch

“Far over the misty mountains cold

To dungeons deep and caverns old

We must away ere break of day

To seek the pale enchanted gold.”

I’ve read some epic fantasy works prior to this. However, if you consider the number-of-pages-to-world-building ratio, or how much world-building gets done in proportion to the number of pages of a book, I have yet to read a book that has as intricate of world-building as The Hobbit did.

The biggest example is perhaps the races of Middle-Earth—they have never felt so distinct from one another, with their own traits, culture, and mythology. Perhaps the biggest difference I felt when compared to other fantasy works.

I mentioned the Elves earlier as an example. Prior to Tolkien, there was no single interpretation of elves—it was scattered in Norse, Germanic, works of Old English, among many others. Tolkien collected and combined many of these interpretations to create the Elves we are familiar with.

To various extents, this is also true for the remaining races and occupations of The Hobbit: the hobbits, dwarves, trolls, goblins, wizards, among many many others.

Something I have yet to be seen used extensively in other works I have read are poems, songs, and rhymes, such as the one I have quoted above. They aren’t just there to flex Tolkien’s background in philology (the study of oral and written historical sources), but also helped highlighted the differences in the races of Middle-Earth:

The less-than-intelligent orcs and goblins sang songs using lots of colloquialism and onomatopeia.

Elves sang songs with hints of Old English and lots of mention of nature, possibly alluding to their near-immortality and connectedness to nature.

Dwarves’ songs pretty much always mentioned silverwares, gold, and other valuables—highlighting their affinity for such treasures.

The Hobbit did a fantastic job at setting up the world that will be expanded later on by Tolkien.

We also learn later in The Lord of the Rings trilogy that Tolkien went as far as devising numerous fictional languages for the books’ various races (which is insane btw). But let’s get to that when we get to the LoTR books.

Straightforward plot and storytelling

“Do you wish me a good morning, or mean that it is a good morning whether I want it or not; or that you feel good this morning; or that it is a morning to be good on?”

While I’m new-ish to fantasy books, I’m not new to the fantasy genre of media—I have played a bunch of fantasy RPG games (Final Fantasy, Tales of, The Witcher, The Elder Scrolls, etc.). From that, I would say that I am familiar to the traditional fantasy storyline.

The Hobbit, to me, is most definitely a very traditional fantasy questing story. Perhaps it’s due to the fact that the story is written for children, and purposefully written to be more like a straightforward fairy-tale plot.

No twists or turns, no extensive characterization, just straight-up adventure.

This carries over to the prose & storytelling as well—quite straightforward, no beating around the bush. It feels like we’re told a lot of things in terms of the plot and characters, rather than shown and convinced.

You could very well compare it to the first Harry Potter book: lots of adventure, great world-building, an old wise wizard, minus the Voldemort reveal at the end.

While it doesn’t make the story predictable, it did make it a less interesting read for me—I did pick up and put down the book more often compared to others, even though this isn’t a very long book.

Bilbo Baggins, the Mary Sue

“Already they had come to respect little Bilbo. Now he had become the real leader in their adventure.”

A Mary Sue character is a character who might be either or both of the following:

An idealized author-self-insert into the story

A character with no meaningful flaws, overpowered abilities, and universally admired

For me, Bilbo Baggins, the titular hobbit, falls into the second criteria.

He seems to have an unusual, inexplicable growth through the first few conflicts. He transforms from this lazy, slothful, home-loving hobbit, to smart, cunning, bold out of seemingly nowhere.

Despite being at least 3 times younger than the dwarves (most are 150+ years old, Bilbo is 50), somehow he seems wiser than them all? What have the dwarves been doing for those 150 years of their lives?

He also stumbles upon an unfair advantage that I won’t spoil here, but without it, I doubt a lot would have gone his way. I think a story becomes less interesting when the main character’s victory is accomplished through lots of external luck rather than their own effort.

But then again, I can’t fault it too much because it’s a children’s story. Children love to see the good guy win spectacularly. In that sense, I think the story has achieved it through Bilbo’s characterization.

Though for me, I still don’t think Bilbo is that interesting of a character.

Final Thoughts

I could 100% see that if you read The Hobbit as a kid, perhaps as one of your first exposure to fantasy, it might be an amazing read.

It certainly has the world-building, the diverse and wondrous cast of characters, and some semblance of a story to support it.

However, if you aren’t a child and you are already familiar with fantasy as a genre, The Hobbit wouldn’t be high up my to-be-read list, unless you want to read it before getting into The Lord of the Rings trilogy.